Design in Practice

In this section, we describe LEEDR’s design process, and how the three sensory ethnographic categories – everyday improvisation, making the home ‘feel right’, and movement through the home – have been incorporated within it.

Rather than prescribing how designers should use these lenses, we show how they framed and came together with other user centred design strategies on the project, specifically interdisciplinary personas and a process we called PORTS (People, Objects and Resources through Time and Space), to help inform concepts for low effort energy demand reduction.

People, Objects and Resources through Time and Space (PORTS)

In our attempts to link perspectives and data from the social sciences, engineering and design, we created new and adapted existing design practices and tools, exploring and designing to how people live out their lives and the energy consuming activities that are part of this.

Download a high-res version of our PORTS diagram.

Our data and existing literature suggested that, rather than isolating and aiming to fix instances of ‘bad behaviour’, it was important to consider the complex mesh of activities and routines in which that problem is embedded. The aim was to facilitate new ways of doing things, or make old ways of doing things more efficient. We began by studying the intersections of ‘people, objects and resources through time and space’ (PORTS) as they emerged from detailed ethnographic narratives, based on our everyday activity visits, and in relation to our households’ corresponding energy data. Within given narratives, we applied ‘freeze frames’ to study intersections in more detail, exploring how they became meaningful or relevant within situated moments.

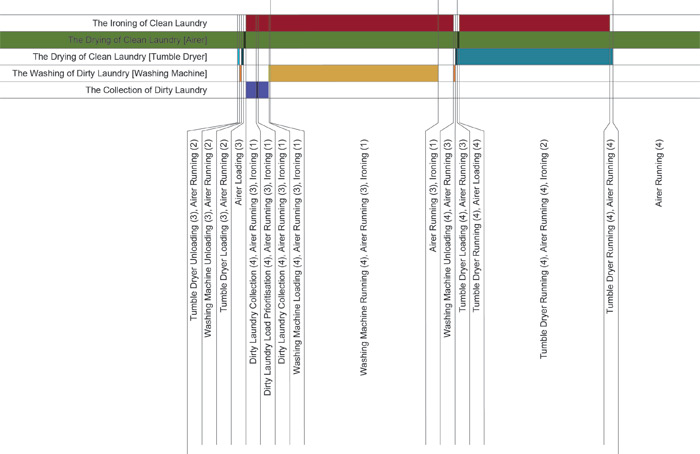

We charted laundry activities over time, and used this to corroborate our ethnographic narratives with appliance energy use.

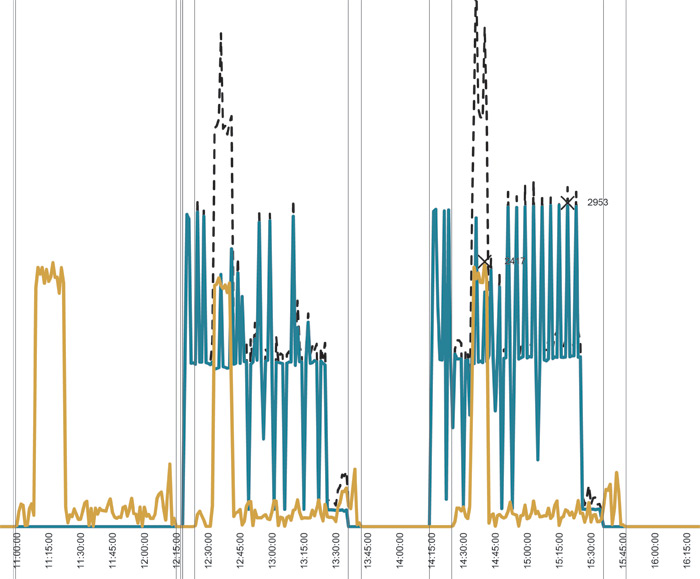

We matched appliance energy use to intersections between energy use and the home over time. This diagram shows peaks and troughs in energy use throughout the day.

For example, we considered in detail the laundry processes of our participants, which often happened in movement, as participants followed laundry routes and routines through the home. We studied who was part of doing the laundry and what role they played as reflective and habitual agents in the laundry process (people), what kinds of materials and technologies were involved (objects), what tangible and intangible resources were necessary (e.g. flows of water, air and light), how laundry processes were timed, managed and experienced by people (time), and where in and around the house laundry happened, which in itself played a part in how the home was made and experienced (space).

An example ‘laundry route’, showing movements of people (orange) and clothing (blue) within the home (red).

We segmented narratives into ‘freeze frames’ at points that our research showed to be pivotal, such as decision-making moments around dirty laundry prioritisation. Within these freeze frames, we considered the complex assemblages of PORTS elements within clusters of activity, in order to explore in detail the meanings, relevancies and implications of the specific intersections of people, objects and resources. This would then help us identify suitable sites and entry points for intervention (such as the substitution, removal, reconfiguring or deliberate rippling of building blocks). Within this process, the sensory ethnographic concepts and insights (e.g. how people improvised in doing the laundry) provided important analytic lenses which in turn unlocked design insights regarding the kinds of interventions that would be meaningful and impactful in a given laundry process.

Personas

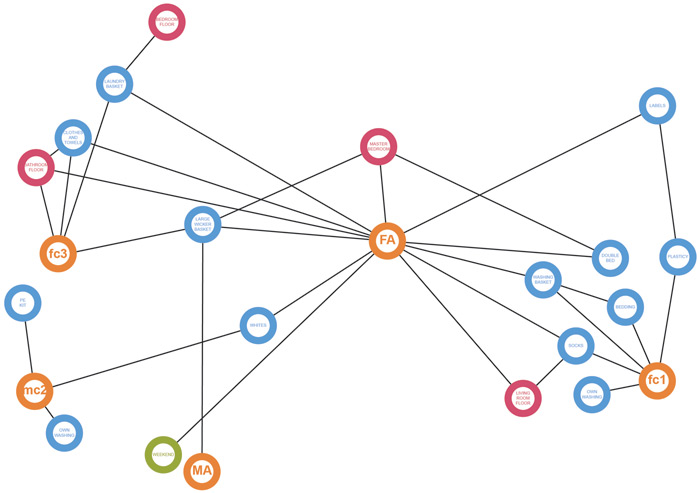

From a design perspective, PORTS provided both a rich source of insights and a headache; each household and emerging ethnographic narrative came with its own idiosyncrasies, so how could we design for twenty different households without providing twenty bespoke solutions?

We used personas to help designers and researchers move between detailed understandings of the ‘real world’ data to wider patterns across households.Download a high-res example.

Personas have long helped designers to move from insights based on the lives of individuals to representing key characteristics of a target market in a way that is relevant to all stakeholders within a project team (see Haines and Mitchell, 2014 for more detail on the use of personas within a multidisciplinary context). Personas are not averages (a persona, like a real family, cannot have 2.4 children!) but archetypes. They provide considered selections and extrapolations – traditionally based on observed behaviour patterns, psychological traits, goals and motivations – which tell a cohesive ‘real world’ story about the fundamental characteristics of a type of person or group of people. They are designed to elicit empathy in a way that designers and others can relate and design to.

As part of LEEDR, we advanced this traditional notion of personas to incorporate both the socio-cultural and material contexts of the home (through ethnographic insights and categories) and the technological, structural and energy-related elements (engineering insights) that derived from our work with the 20 family households. We were still abstracting towards types of families, but these types were firmly rooted in our interdisciplinary data and also allowed for the kinds of dynamics and contradictions that often characterise families and family life in the real world.

Rather than using a traditional coding and clustering approach, we worked more discursively across disciplines, again starting with ‘stories’ from our research. We grouped households according to key variables and connections between participants. These groupings then formed the basis for family personas, which were fleshed out with clustered variables as derived from the designers’ ‘Getting To Know You’ interviews (see Mitchell et al. 2014 for a more detailed description of these design research activities). Three layers of analysis followed – a primary immersed layer (life stages, status, values and technology); a secondary coded layer (energy, sustainability and the future); and a tertiary coded layer (family and house background, occupancy and family dynamics, perceptions of others).

Again, we used laundry as an initial example and created personas across three boards: a context board with overall persona characteristics and relevant quotes from participant families; an overview of selected laundry technologies, systems and typical consumption statistics for each persona; and a concise PORTS laundry narrative, incorporating and making sense of the data from all three disciplines: engineering, design and social sciences). Graphs and statistics were included as visual representations of actual data profiles for appliances carefully selected and adjusted to convey the persona family’s laundry characteristics in a tangible and believable way.

These personas helped us as researchers and designers to move between detailed understandings of ‘real world’ data to wider patterns across households. As such, they became investigatory tools through which to generate new insights and design concepts.

Design Concepts

While the development of PORTS narratives and personas had already been an interdisciplinary effort, the LEEDR designers were keen to generate concepts with the help of the wider team during a number of design workshops. Not only did this allow for a richer pool of viewpoints and ideas, it also helped to continue drawing attention back to the insights and categories that had developed during the analysis of our datasets, while at the same time using PORTS and the interdisciplinary personas to focus our attention and not get lost in too much complexity.

Taking a user centred design approach, we followed an ideation process moving us from insights to opportunities in order to create digital interventions that could help householders reduce domestic energy consumption with minimal effort.

Amongst the interdisciplinary team, opportunity statements were generated on post-it notes under each insight. Each statement began with ‘How might we…’, for example: How Might We bend perceptions of time in order to reduce a family’s energy consumption.

We then selected a number of key HMW… statements of interest across the project team before beginning the concept design phase, creatively framing and exploring the solution space through the rapid generation and convergence of a breadth of concepts in response to the identified opportunities. Below we introduce five design concepts that were derived from this systemic approach to generating insights and opportunities.

KAIROS

Kairos, a term the ancient Greeks used for the opportune moment, is a mobile app concept that allows the user to set a delayed end time and intelligent profile for their appliances and heating system that is grounded and situated within their daily lives. The KAIROS concept links to the insights: everyday improvisation and making the home feel right.

Anima

Anima is a proxy for the heartbeat of the home, designed to draw the household into considering the energy use of the home in terms of its ‘health’ or ‘fitness’, rather than using abstract energy or ecological metrics, such as Kilowatts or carbon units; units which have been shown time and again to be intangible to the everyday user. This concept is inspired by insights relating to ‘making the home feel right’.

Future/Self

Future/Self is an opportunity to bend time. Future/Self is an app that allows you to commune with your own future self; be guided with your own seasoned words on your own big life decisions. When should I have a baby and what do I need to do to be ready? Is now the right time to invest in solar panels? What will happen if I let my parents move in with me? Through Future/Self, we have explored how the concept of ‘life stages’ and ‘bending time’ can be used to pro-actively inform an individual or family on an activity in order to be more time efficient and to save energy.

Finite

Finite is a goal setting app and investigative tool for the family, shifting the conversation from the infinite, ‘how much have I consumed?’, to the finite, ‘how much do I have left?’

Hinterland

Hinterland is an augmented reality app that makes the invisible, visible. Using a tablet as a viewing portal (with an underlying network of smart plugs and RFID tags), the app illustrates in real-time energy consumed as a series of industrial cloud plumes emanating from host devices.

Astitchin

Embracing the idiom ‘a stitch in time saves nine’, we propose Astitchin time, can save the weekend. Astitchin is an app concept that ties energy saving with personal life goals, visualised as a family calendar that distorts and restores a treasured family photo depending upon your scheduled (or routine) use of relevant resources.